Dear Cousin Jennifer,

Had I lived, I would have been one of your father’s many first cousins. I’m touched to know that I have not been forgotten though your father last saw me when I was sixteen. Back then, I was tall. I looked people in the eye. I spoke from the heart. I was brave.

I had hoped to immigrate to New York like my older brother. He left Röddenau in May 1938 with our grandmother. I had begged my parents to send me with them. But they could only bear to part with one child, and I had to stay home. They told me my time would come.

My opportunity was the Kindertransport to Belgium with your father. Mechelen, Belgium was not New York. But I shouldn’t complain. My younger sisters, Anneliese and Hilde, never even saw Belgium.

Anneliese and Hilde @ 1941Though I would tell people that I was a happy child, I was not ignorant of the politics of my times. The first problem I remember came when I was nine in 1935. It started with rumors at school. A boy a year behind me went to the police and accused Father of having mistreated him. Officials in town forced Father to walk around town the following Saturday with a sign that said, “I am a Jew.” Father had customers before who had argued with him from time to time. But nothing like that. Imagine - a young boy had the power to cause Father’s public humiliation. It was after this that my parents and Grandmother tried to set the wheels in motion to immigrate.

Then, several months after Grandmother and my brother arrived in New York, it was Kristallnacht. “What now?” Father said, when he heard banging on the door in the middle of the night. “Did something happen at the store?”

“Come with us,” shouted the SA-men outside. “Now!” I watched from the top of the staircase as Father was dragged from the house in his robe. I didn’t say goodbye. Mother went to the police station the following day with a suitcase of clothes for him.

You can learn today much more about the events of November 1938 than what I knew at the time. What I knew was that Father was gone, first to the Röddenau jail and then to Buchenwald, and that other Jews in the area had been arrested.

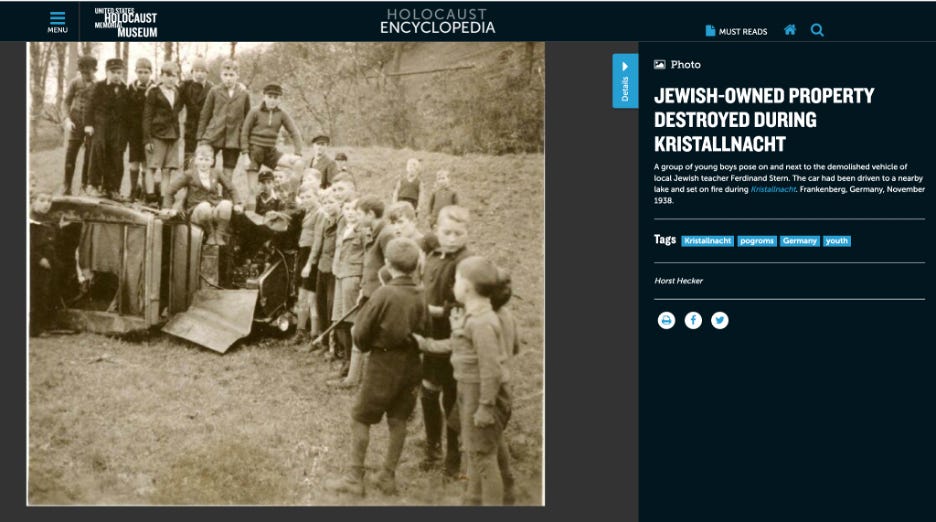

Several decades after the war, a local historian, Horst Hecker combed through local files to find out what happened to all of us Jews. He sent the picture below to the US Holocaust Memorial Museum. It looks like school boys out for an afternoon. But read the caption: the boys had been involved with looting a car of our Hebrew School teacher, Ferdinand Stern. Stern had helped prepare my brother for his Bar Mitzvah. We all knew, and respected, Lehrer Stern. Hecker was beaten by the local police and died in Buchenwald.

Otto Lorenz, a policeman in Frankenau, was responsible for beating Lehrer Stern and destroying the car. If he didn’t do it personally, he ordered others to do it.

Isidor Oppenheimer (the brother of my uncle / your great uncle Max Oppenheimer), wrote a letter to someone in Frankenau after the war asking what became of Lorenz, and whether he had been punished for his actions. Other Jews from Frankenau who’d survived (including Max Oppenheimer) wrote letters testifying against Lorenz. Eventually, he spent some time in prison. But he died in his home having received a pension in his old age from the government for his service.

Maybe I should have just stayed home with Mother and my younger sisters. All that studying I did in Belgium, my efforts to study Flemish, to make friends, to adapt, where did it get me? Not to New York.

And I wasn’t home with Father when he died. Mother and my sisters were with him. He’d come from Buchenwald sick - partially it had been the beating, partially they said he had liver cancer. I felt terrible not being there. I was ignorant of his poor health. Neither Mother nor Father wanted me worried.

Then the telegram arrived: “Father died. Come home.”

Mother’s sister, our Aunt Hertha, and our mother’s mother, Grandma Rosalie, came to live with us. But there was no school. There was nothing to do but read books over and over.

In December 1941, we received papers that we were going to Riga. I looked on a map in an old school book: Riga was quite far east of Germany. What could the Nazis want from us there, I wondered. Mother told Anneliese and me that if they asked us to work, we should say yes. Yes, we can sew. Yes, we can clean. Whatever they need, we can do it. We were to obey, to do whatever they said, to not be beaten. Mother, herself, wasn’t feeling well.

But then, we didn’t have to go to Riga. They left us alone. I kept rereading the books that I’d already read.

At the end of June 1942, Aunt Hertha got a letter that she and Grandma Rosalie should report to Dortmund. It was unclear if they’d then be traveling to Riga or somewhere else.

Aunt Hertha was afraid for my sisters and me because Mother was still sick. She went to Mayor Eckhardt and pleaded that we should all be together. Mayor Eckhardt arranged that all of us should go together to Dortmund. A truck came to our house for us. Off we went. Someone else moved into our family house.

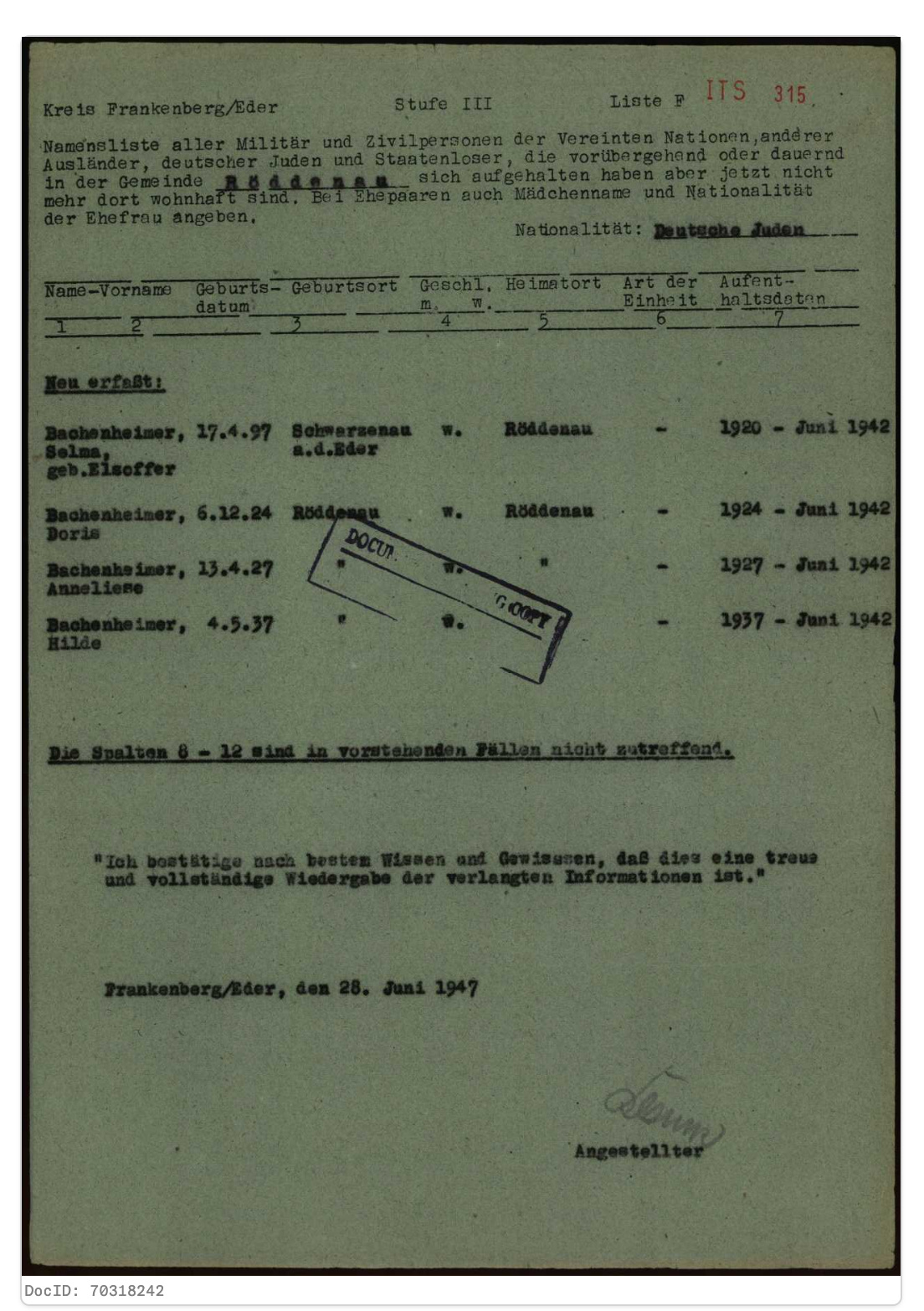

This documentation from the UN (June 1947). It shows Doris and family were gone from the old family house in Röddenau in June 1942.

Dortmund is only seventy-two miles from Röddenau. But sitting in a truck without windows, those miles seemed long. I held Hilde, who was still only five years old, on my lap so she wouldn’t cry. I held her head next to my chest so she could hear my heart beating, hoping to calm her.

We stayed in an overcrowded jail in Dortmund for several days. There were not enough beds, not enough food, not enough toilets. Why? Hilde asked me all day long. Why were we here? I didn’t have anything to tell her. I was asking myself the same question. What had we done? Why were they treating us like criminals?

After several days like this, we were relieved that they gave us train tickets. We were going on train X/1 to Theresienstadt. Mother was ticket 809, Hilde 810, I was 811 and Anneliese was 812. We knew Theresienstadt was a bad place, a concentration camp for Jews.

As we went to get on the train, the horrible police screamed at us. This caused everyone to push and behave in a disorderly fashion. Not surprisingly, the train car was something old with broken seats, plus there were not enough seats for all of us. After I helped get Mother, Grandmother and Aunt Hertha seated with Anneliese and Hilde, I helped an woman in a wheelchair. I had never helped maneuver a wheelchair before. It took six of us, hoisting and pulling the wheelchair, to get the poor woman safely on the train. She was crying and hid her face in her hands. Although some of the people were annoyed at me for trying to help her — I was cursed at more than once — I somehow maneuvered the wheelchair next to the rest of my family. Anneliese now had all our suitcases in her lap. Hilde was sitting on mother. There was no room for me to sit.

Once the train started moving, the woman in the wheelchair stopped crying. I patted her on the shoulder. She said, “Thank you!” in a soft, but kind, voice. I smiled at her. She lifted her face out of her hands.

Mother looked at her. Mother asked, “Adele Krebs?”

“Yes,” said the woman. It turned out that Adele Krebs and Mother had gone to school together as children. Adele Krebs, I learned, was an aunt to your father. She was your grandfather’s sister. She had come by herself because the rest of the family had already left Berleburg.

“I am so sorry about your husband.” Adele said to Mother. “So sad.”

“You knew my father?” asked Hilde.

“Yes, of course,” said Adele.

Hilde asked Adele if her legs hurt her, if that was why she was in the wheelchair. When Adele said no, Hilde climbed onto her lap. Then Hilde yawned and fell asleep. Chatting with Adele helped us pass the time. Adele had a few sandwiches, which she very kindly shared. Grandma Rosalie shared the rest of the food we had brought with us. There was not much anymore, just a few apples and some dry toast.

Eventually, the train pulled up to a platform with a sign for Theresienstadt, or Terezin in the local language. I held Hilde’s hand tightly until she was down from the train. Then I, and several others, helped the sick ones off.

We stayed in Theresienstadt for almost six months. Grandma Rosalie died after less than a month. Perhaps it was the food. They offered us little, and she barely ate anything. She usually gave me hers, telling me that I had to grow. It was my time to fill out and blossom.

The only thing that seemed to blossom in Theresienstadt was a tilia tree that grew outside of our barracks. Tilia is a common tree, but I hadn’t spent much time looking at trees before. The tilia has heart-shaped leaves. By the end of August, it had flowered, small white petals hanging off each branch. Someone in the camp said that you could drink an infusion of its flowers. We tried this and it was very fragrant, a very good cup of tea. We gathered as many flowers as we could and brewed the tea with as much sugar as we could find. The tea was like a small present for anyone who drank it. Then in early September, the Tilia fruited, up high of course, because we had picked all the flowers we could reach. The fruit looked like little green cherries. I hoped someday that they would turn red, and we could eat them. No such luck.

As the days became shorter, the Tilia tree’s leaves turned to yellow. Then they littered the ground. I cried the day that the tree was completely bare, as if I had lost a friend, or maybe for lost time, or maybe because that day Anneliese began coughing.

In January 1943, we were again given tickets, this time for Auschwitz. My sisters and I cried when we had to say goodbye to Adele Krebs. She was too sick to travel. Although I don’t think anyone believed it, we said, “See you in New York” as if it was Passover and we were saying, “Next year in Jerusalem.”

You know the rest of my story. It is told in statistics. Per Yad Vashem:

The transport, designated “Ct”, departed from Theresienstadt on January 29, 1943 and was the fourth of a series of five transports. On board were 1,000 men, women and children. It arrived in Auschwitz the next day on January 30.

On the day of the transport, the inmates were marched to the Bauschowitz (Bohusovice) train station, some 3km outside the ghetto, where they were loaded onto the railway cars that were waiting. Those unable to march were taken with the heavier luggage by truck or by man-drawn carts.

The train from Theresienstadt to Auschwitz, which was designated “Da 107”, went north to Dresden, and then east to Breslau (Wroclaw) and Kattowitz (Katowice). The empty train returned to Theresienstadt under the designation “Lp 108”.

Upon their arrival in Auschwitz, the inmates were divided into two groups, men in one, and women with children in the other. According to historian Danuta Czech, 122 men and 95 women were deemed fit for labour and were taken into the camp: the rest were marched off to the gas chambers in Birkenau where they were murdered.

According to historian H. G. Adler, only 23 people from this transport are known to have survived the war.

Please remember me to your father. To think, he is still walking the earth….

With love,

Cousin Doris

(below wearing plaid, of course)

I love Doris' story. And starting with "Had I lived" throws a poignant cast over the whole piece. Yet, the story is enhanced by the first person POV. You're such a thoughtful writer.

Thank you Jen. This is beautifully written with so many facts woven in. Your research and your connection to your family brings Doris and her story come alive for me. It is heartbreaking.