A curator at the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum receives an unusual donation: a photo album discovered decades earlier in Germany. Unlike official propaganda photos, these are candid shots taken by an amateur with a pocket camera. They show SS officers at Auschwitz—smiling, eating, relaxing. No corpses. No smoke stacks. No prisoners. Just ordinary-looking off-duty soldiers.

One image shows young women eating blueberries, captioned "Hier gibt es Blaubeeren"—"Here there are blueberries." That haunting line becomes the title of a Moisés Kaufman play that I recently saw at Berkeley Rep.

The story unfolds like a detective case. Who took the photos? What were the people thinking as they posed just beyond the killing machinery? The curators piece together names, dates, and locations, tracking down the lodge where women sat with bowls of fruit, the smokestacks nowhere to be seen.

What struck me most wasn't the horror—it was the banality. Hannah Arendt's phrase came to mind. When descendants of Nazis recognized their ancestors in the photos, they didn't defend them or claim they were misunderstood. They accepted the truth of what their relatives had done. They tried to reconcile the men they knew with the acts they had done.

Which made me think: If Nazi descendants can acknowledge their ancestors' evil, why do so many Americans fear their children will be harmed by a discussion of the evils and consequences of slavery? Why have so many states banned classroom discussions of slavery and/or attempted to justify it?

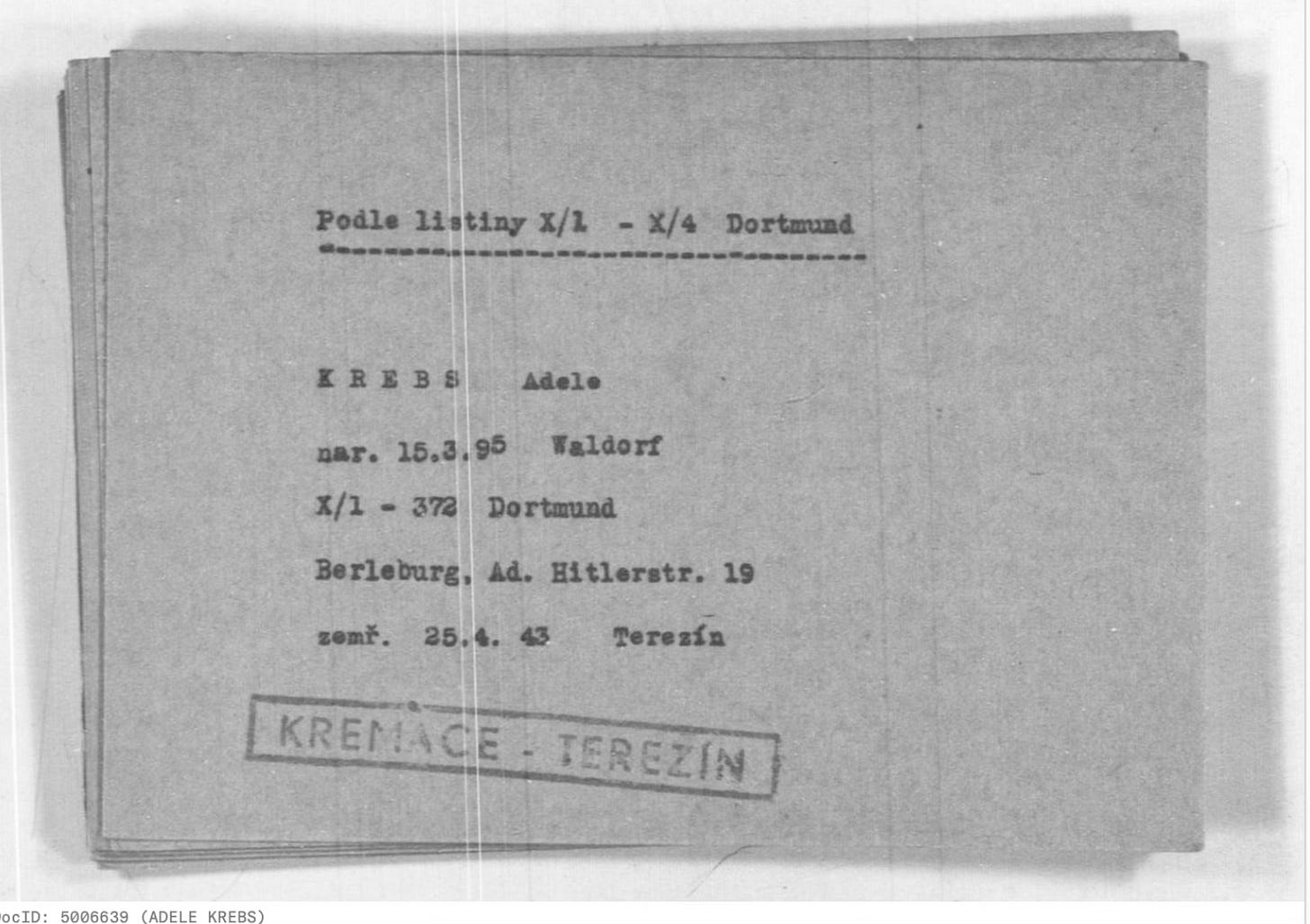

While researching my book Stumbling Blocks, I spent months tracking down what happened to family members who didn't escape Germany. The work was often tedious—databases, translation programs, scattered files. But then something would spark: I discovered that my grandfather's sister Adele and my grandmother's sister-in-law Selma, along with Selma's daughters, were deported on the same train to Teresienstadt. Adele and Selma had grown up in the same town, and probably knew each other from school or synagogue. Maybe they sat together on that train, comforted each other, and made the journey slightly less unbearable.

That imagined story—two women who'd attended the same weddings and birthday parties, now facing the same fate—transformed dry research into something human and heartbreaking.

Here There Are Blueberries reminded me why such work matters. Not for neat moral conclusions, but because we wear our ancestors' shoes. Evil isn't always dramatic—sometimes it's a row of women smiling with fruit, women who haven't thought once that day about the smoke rising nearby or why trains full of people keep arriving.

Unless we recognize ourselves in those women, our great-great-grandchildren may wonder why we kept so quiet.

This is so beautiful and profound ❤️

Thank you for this work and all the time and devotion you poured into it.

We saw a production of "Here There are Blueberries" at the Shakespeare Theatre in Washington, DC and it is particularly appalling to see evidence of ordinary people enjoying treats after spending their days facilitating mass murder. Seeing the deportation cards for your relatives is shocking in its banality. I also felt chilled by noticing that Selma's birthday was 17 April 1897 - our grandson was born on 17 April 2025 and our own country is currently engaged in cruel deportations of "undesirables."