Schadenfreude is my Word of the Day, an email tells me. It’s still opaque to me how and why I receive this Word of the Day subscription, who selects the words, and why I can’t quite hit the unsubscribe button.

Schadenfreude? You’d think I might have learned that word as a child. After all, the way people treated Uncle Adolf, he practically epitomized the word. But no, I didn’t.

My mother used an umbrella term, “mixed emotions”, to cover everything from ambivalence to vacillation, a vast territory, which might have included Schadenfreude. Carnival rides were fun and scary. Movie endings were bittersweet. Performing in front of an audience was exhilarating and terrifying.

Survivor guilt, a term which fits neatly under my mother’s umbrella, was another word that no one used during my childhood. But that doesn’t mean it wasn’t in the air. Survivor guilt in German in Überlebensschuld-Syndrom. If anyone used this word in my presence, those seven syllables went straight over my head. I could see my paternal grandparents faces etched by layers fear, sadness, self-blame/guilt, anger, shame, and many other emotions that were too complicated for me to name. I knew Dad and his sisters suffered from insomnia.

A website on destroyed German communities states, “Between 1934 and 1942, 13 Berleburg Jews relocated to other towns and cities in Germany. At least 10 Berleburg Jews immigrated, six of them to the United States. On April 28, 1942, three Jews were deported to the East; and on July 27 the last 15 were sent to Theresienstadt.”[1] Likely, any Jew who my grandparents, aunts and dad said goodbye to in May 1941 when they fled Germany for good, went to a concentration camp. Only Goldschmidt, the town butcher, came home alive.

I don’t think anyone meant to deceive me about what happened to those left behind. But I’m sure the stamina required to answer my questions was not always there. Thankfully, now I can consult the hive-mind of the internet and not bother anyone.

I plugged various facts about Uncle Adolf into various Holocaust databases. These included my father’s memories of the day after Kristallnacht, and Adolf being taken away in a bus with the rest of men from Berleburg to the Oranienburg Concentration Camp. [1]

I had memories of a conversation with Aunt Lucie in which she told me that Grandpa was worried that hot-headed Adolf was going to get killed in Oranienburg. Grandpa applied to a Jewish organization on his brother’s behalf so that Adolf could go to England. There, he was to get visas for Betty and Ruth. But, per Aunt Lucie, England arrested Uncle Adolf as an enemy alien. He had no way to make a living or get anyone a visa.

Aunt Hilda later told me that Uncle Adolf got sent off to Australia.

When I searched for “Adolf Krebs immigrant England,” I found much biographical information about Hans Adolf Krebs, famous for the Krebs Cycle. It turned out that Hans Adolf was born the same year as my uncle roughly 150 miles away. When the Nazis came to power (January 1933), Hans Adolf was fired from his university hospital post for being a Jew. He received plenty of job offers abroad and selected one at the University of Cambridge. He was never arrested in England as an enemy alien.

Eventually, I stumbled across a website that listed Dr. Rachel Pistol, author of Internment during the Second World War; A Comparative Study of Great Britain and the USA (Bloomsbury Press, 2019), as a contact. I reached out to her to find out if Uncle Adolf had turned up in any of her research.

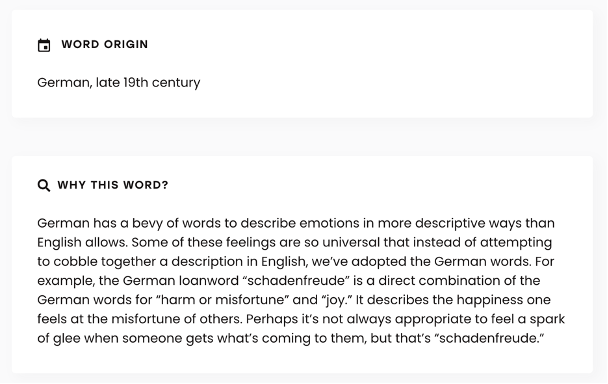

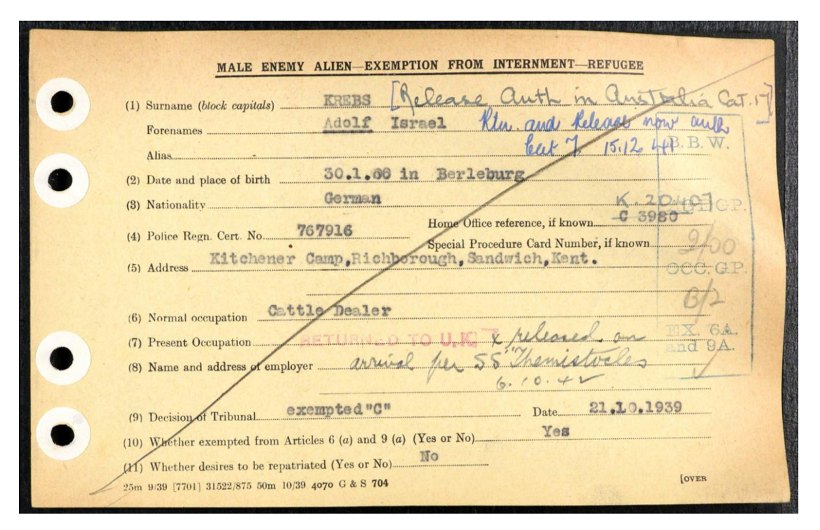

Dr. Pistol was located in England. She had access to a variety of lists of German Jewish internees. She sent me back several documents. A document entitled MALE ENEMY ALIEN – EXEMPTION FROM INTERNMENT – REFUGEE clarifies, that yes, Adolf had been arrested in England as an enemy alien. The date of the decision of the tribunal is listed as October 21, 1939, surely not too long after Adolf’s arrival. Uncle Adolf’s address on the form is listed as Kitchener Camp in Kent, England.

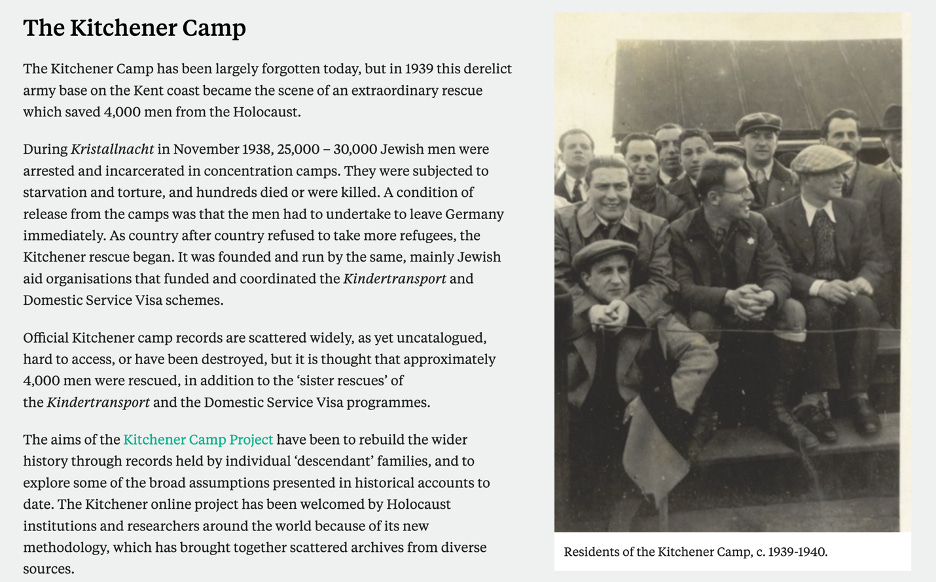

I looked up information on Kitchener Camp on several websites. It is fairly widely known in Britain. Several thousand German Jews lived there starting in January 1939. A website announcing a concert at the camp in 2022, says:

The camp operated like a small town and had its own post office, hospital and cinema. Music became hugely significant and as more refugee musicians arrived, a camp orchestra was formed. Such was the orchestra’s reputation that arrangements were made in August 1939 for a live BBC broadcast of one of their concerts. The onset of war unfortunately scuppered these plans. But now, over 80 years later, and around the corner from Broadcasting House, the Wigmore Hall will symbolically stage the BBC Kitchener concert that never took place. With narration from Jon Sopel and Emily Maitlis, and music from the Ensemble 360 String Quartet and the London Cantorial Singers, the concert will honour those who established the Kitchener Camp, as well as the memory of the millions who were not able to find refuge from the horrors of Nazism.

The event will conclude with the awarding of British Heroes of The Holocaust medals to descendants of brothers Jonas and Phineas May, and Ernest Joseph – three men who played pivotal roles in establishing and running the Kitchener Camp.[2]

Some men from the camp volunteered for the British army. Some stayed in England after the war. Uncle Adolf’s name appears on the camp’s website. Perhaps he was accepted to go there because had agricultural experience. The screenshot below from the Wiener Holocaust Library (in London) shows men in the camp and offers a bit more information:

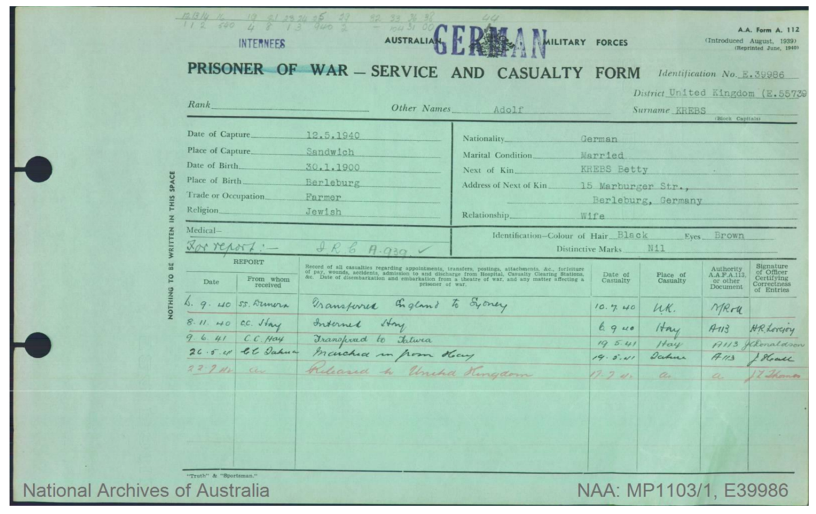

Dr. Pistol also sent me a Prisoner of War -- Service and Casualty Form, which is stamped National Archives of Australia on the bottom. This form documents Uncle Adolf’s transport by ship to Australia, and the names of two different internment camps where he was detained as an enemy alien. He arrived in Sydney in September 1940; was interned first at the Hay Camp (November 1940 to June 1941) and then at the Tatura Camp (June 1941 to July 1942). Both camps are in New South Wales a bit north of Melbourne.

The first form seems to indicate that in December 1941, Adolf may have been authorized to return to England. The red line on the second form indicates that Adolf was released back to England in July 1942. Why it took so long after the authorization for Adolf to be returned to London is not clear.

Dr. Pistol also confirmed (and the second form lists) that Uncle Adolf was on the well-known ship, the Dunera. Some of the “Dunera Boys” stayed in Australia after the war and became immigrant strivers/success stories. But their voyage did not begin auspiciously:

One of the best-known episodes of wartime internment is the story of the HMT Dunera (Hired Military Transport). In July 1940, the Commonwealth government agreed to accept 6,000 internees from the United Kingdom. However, only one shipment was dispatched to Australia. On board the HMT Dunera were about 2,000 male German Jewish refugees aged between 16 and 45, who had escaped from Nazi occupied territories. Also on board were 200 Italian POWs and 250 Nazis.

The voyage lasted 57 days. The conditions were appalling. Apart from overcrowding on the ship with the attendant problems of hygiene and harsh treatment by crew members, the journey was also made unpleasant by the fear of torpedo attacks, the uncertainty of the destination, and by tensions between Jewish refugees and Nazi passengers.[3]

I locked another piece in place in the puzzle of Adolf’s war years: He left Germany for England in 1939. He was interned at Kitchener in October (or earlier). In July 1940, he was loaded on a boat for Australia where he lived successively in two internment camps until July 1942, when he was returned to England. During none of this, could he possibly have helped Betty or Ruth. In fact, he might not have received or been able to write mail during this time. It is possible that Adolf had no contact with any family members.

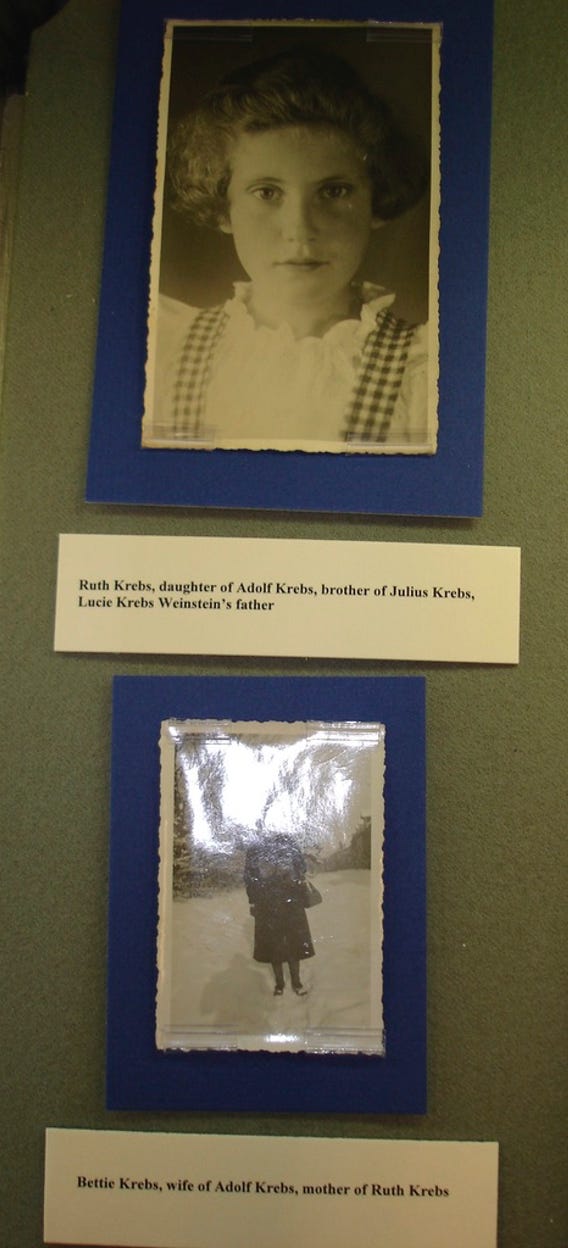

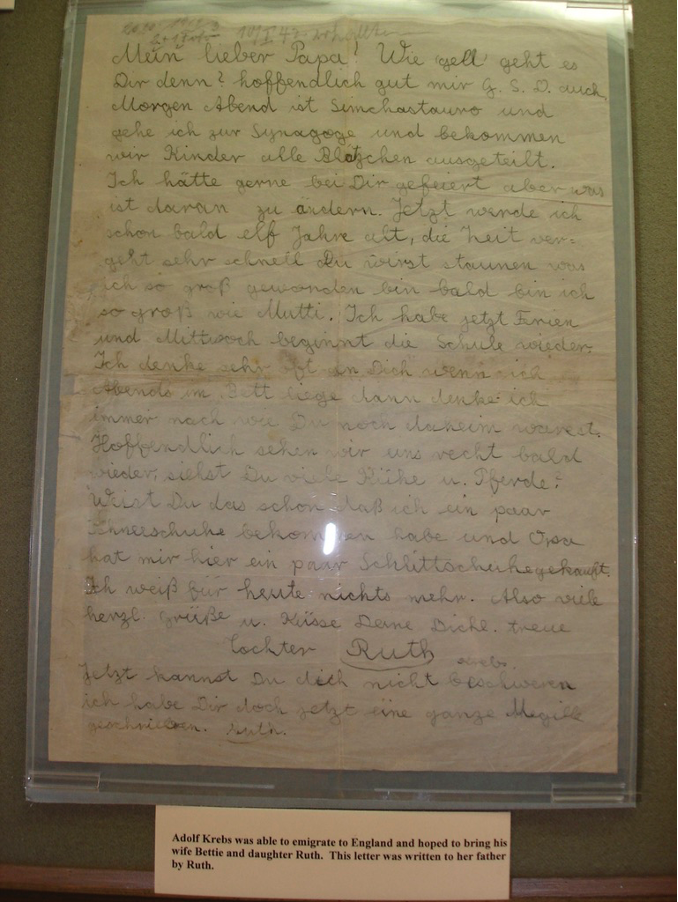

A source from Berleburg (I don’t know the name of this witness) stated that Adolf’s daughter Ruth sent her father a letter that he didn’t receive until after the war. (The letter can be found at the end of this post.) The witness’s testimony informed an audio play about Ruth and Betty, which can be found on the Westphalia Stolpersteine Website. The script for the play (translated by Chat GPT) is also at the end of this post.

The narrator concludes, “Ruth's father, Adolf Krebs, received the letter only after the war. When his daughter and wife wrote to him, he was in English captivity in Australia. Betty Krebs was deported from Frankfurt and is considered missing. There are indications that in 1944, as a 13-year-old, Ruth was deported to the Theresienstadt concentration camp and was murdered in Auschwitz the following year.”

Aunt Hilda heard some version of this when she visited Berleburg in 1999 for the dedication of the memorial to the Jews from Berleburg killed in the Holocaust. The thought of Ruth going alone to the gas chambers gave her nightmares. Aunt Hilda wrote to her children:

Ruthchen, my little cousin was beautiful with blond hair and blue eyes like a typical German girl. She always wanted to be near me since she had no one to play with. She admired me because I was older. I found out later that she went to the concentration camp by herself separated from her mother and grandparents, never to be heard of again.

It is not clear that Hilda’s nightmare was, indeed, Ruth’s fate. The German Federal Archives book, Victims of the Persecution of Jews under the National Socialist Tyranny in Germany 1933 – 1945, which is used by Yad Vachem as documentation of the fate of many killed in the Holocaust, indicates that Ruth and Betty were deported to Sobibor together from Frankfurt on June 11, 1942. But even if Betty and Ruth were deported together and went to the gas chambers together (or some other death at Sobibor together [firing squad?]), their deaths were brutal and senseless. They were not the only ones harmed by their deaths. The harm reached out far beyond the crematoriums of Poland all the way to Spencerport, New York, all the way from 1942 to the current day, generation to generation.

Finding these answers to my questions about Adolf has brought me a bit more understanding about the tragedies in his life. Yet, I still don’t feel I knew the man. Was he a goof or a Goniff? Was he a good father? Was he good to his cows? Did he love Aunt Erna (who he eventually walked out on)? Did he hate himself? Do the answers lie in survivor’s guilt? Or something that preceded the Holocaust? I can think of a dozen more questions I won’t be able to get answers for. But now that I’m no longer eleven, I realize how much in the world is uncertain and unknowable. And I can almost live with that fact.

ChatGPT translation of Audio Play, Für heute weiß ich nichts mehr / For today, I don't know anything else Take me to the website

Ruth (10) and her mother Betty (40) at the kitchen table in Frankfurt (Main) 1942, Ruth is reading (writing) a letter, and Mother is washing dishes.

Ruth: Frankfurt am Main, 01.10.42 My dear Papa! How are you? Is Mutti doing well?

Betty: A solid start.

Ruth: What if he's not doing well?

Betty: He's doing very well, he drinks tea every day.

Ruth; Why?

Betty: Everyone drinks tea in England. With milk.

Ruth: Ugh!

Betty: And there, Ruth is pronounced RuTH.

Ruth: I'm called RuTh (laughing). When we're together again, I'll be RuTH!

Betty: Exactly. And what else?

Ruth: (writing) How are you? Hopefully good. Tomorrow evening is Simchat Torah, I'm going to the synagogue, and we children will get cookies. There will be cookies, right, Mom?

Betty: Certainly. Probably.

Ruth: (continues writing) I would have liked to celebrate with you, but there's nothing to be done about it. I'll be eleven years old soon, time passes very quickly; you'll be amazed at how much I've grown.

Betty: (laughing) Really?

Ruth: ...I'll soon be as tall as Mutti.

Betty: No!

Ruth: Yes! Look...

Betty: You are least two fingers' width shorter than me.

Ruth: (laughing) No! You're not allowed to stand on your tiptoes.

Betty: (laughing) Yes!

Ruth: Well, but when I see Papa again, then it will definitely be true... When are we going to England? Or America?

Betty

We'll see. It's expensive, Ruth. What did you write after that?

Ruth: I think of you very often when I lie in bed at night, I always think about how you were still at home. There was always food, and I could go to my regular school. Do you know that now all the cousins are also living with Grandma and Grandpa in Frankfurt? We're not allowed to go to any other schools anymore! And Aunt Adele is not allowed to manage the Edeka anymore!

Betty: No, Ruth, please don't write that.

Ruth: Everything from there?

Betty: From "There was always food."

Ruth: So he won't be sad, right?

Betty: Yes.

Ruth: For today, I don't know anything else. So warm regards and kisses, your loving and faithful daughter Ruth. Hm. P.S.: Now you can't complain, I've written you quite a lot now. RuTH (English pronunciation).

Narrator: Ruth's father, Adolf Krebs, received the letter only after the war. When his daughter and wife wrote to him, he was in English captivity in Australia. Betty Krebs was deported from Frankfurt and is considered missing. There are indications that in 1944, as a 13-year-old, Ruth was deported to the Theresienstadt concentration camp and was murdered in Auschwitz the following year.

Googling Adolf Krebs, I learned (or perhaps relearned) that Hans Krebs, the biologist/physician renowned for the Krebs Cycle, had the middle name Adolf. Hans Adolf was born the same year as my uncle roughly 150 miles away. Also like my uncle, Hans Adolf went into his father’s profession. When the Nazis came to power (January 1933), Hans Adolf was fired from his university hospital post for being a Jew. By July 1933, he had accepted a new post at the University of Cambridge. He spent the rest of his life in England, receiving the Nobel for his work in 1953, and a knighthood in 1958. (Hans Adolf Krebs shared his Nobel with Fritz Lipmann, another German Jew who emigrated to the US in 1939.) Lastly, Hans Adolf was never arrested as an enemy alien by the British.

When I googled Erna Joseph, Aunt Erna’s maiden name, I found records for a nurse named Erna Joseph who worked at the Jewish Hospital in Berlin. I never knew Germany had Jewish hospitals so I looked for more information on the hospital. A visit to the Berlin Jewish hospital’s website in 2023, announces that the hospital is 260 years old! An article on the Traces of War Website, says that the hospital stayed open during the entire Second World War, serving as a hospital for Jewish and other sick people, a deportation depot, and a residence for Jews collaborating with the Gestapo. I imagined that my aunt had once worked at this facility. What stories I must have missed! Then I spoke to my dad. He said my aunt was born in Gelsenkirchen. Erna Joseph, the nurse, was born in Leipzig.

copyright 2023 Jennifer Krebs, jennifer.krebs@gmail.com

[1] Dad’s interview was conducted by the Fortunoff Yale Holocaust Oral History Project on August 2, 1999. A rough synopsis of his remarks pertinent to Adolf is as follows: The day after Kristallnacht, my mother sent me to check in on the other Jewish families in town. All the Jewish men had been arrested and brought to the local jail. My Aunt Betty gave me socks for my Uncle Adolf. She wanted me to bring them to the jail for him. As I got to the jail, a bus pulled up. On it were all the Jewish men from the neighboring towns. They made everyone from the Berleburg jail get on the bus. This included my Hebrew school teacher, a wounded World War I veteran could who was lifted onto the bus on a stretcher.

[2] https://www.gov.uk/government/news/remembering-kitchener-camp-a-memorial-concert-for-yom-hashoa

[3]https://www.migrationheritage.nsw.gov.au/exhibition/objectsthroughtime/dunera/index.html

I wept when I came to the part about Ruth's fate.

This is an amazing account of ordinary people struggling to survive in a nightmarish world. The brutality of the Nazis never ceases to shock me. Although we are all familiar with the history, I think it is more searing to read the stories of individuals. It is heartbreaking to think of young Ruth writing to her father with hope of a rescue and to discover that she died in a concentration camp without ever seeing him again. For him, it must have been both a consolation and a deep sorrow to receive that letter after the war. Your father's descriptions of what happened to him as a boy - from teasing and outright bullying instigated by his teacher, to the Kindertransport trip to Belgium and the long walk to try to escape the Nazi invasion - frames the progression of the ongoing dangers and persecution Jews faced. It is incredible that he maintained his own humanity and even his sense of humor through such a calamitous upbringing.